Covid-19 has—among other things—illustrated just how tethered our economies remain to fossil fuels.

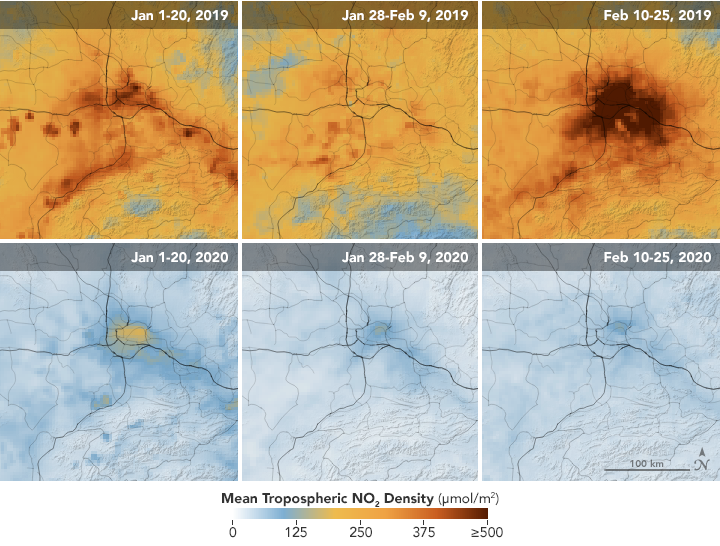

Since countries began locking things down to combat the spread of the novel coronavirus, known as SARS-CoV-2, their emissions have dropped precipitously. In the air above Wuhan, China, levels of nitrogen dioxide, a pollutant produced by burning fossil fuels, vanished as factories closed for Lunar New Year. But after the pandemic set in and the government quarantined the region, they never rebounded. Between February 10–25, NO2 levels were less than a quarter what they were before the holiday. (NASA and ESA satellites captured the change.)

The same thing happened in Italy. The industrial regions in the north have been among the heaviest hit, and NO2 levels tell a similar story. Before the quarantine, they were among the highest on the continent. But once people were restricted to their homes, the region’s air quickly cleaned itself up.

Even though the air in these regions has cleared recently, decades of pollution could be partially to blame for why Covid-19 seems to be hitting older populations harder.

Younger people do get the disease, though, and it tends to be milder. Cases seem to be the mildest among children, consisting of a fever, runny nose, and a cough. In other words, what many kids have most of the winter. One attempt to explain the discrepancy, and one that suggests the role of air pollution, is known as the “pristine lung” hypothesis. Healthy children, who have yet to be subjected to a lifetime of pollutants and particulates, have pristine lungs and no history of inflammation. “The non-inflamed lung is a much less hospitable place for any virus to land,” Buddy Creech, an infectious disease pediatrician at Vanderbilt University Medical Center, told Wired.

When the virus hits the lungs, that’s when things seem to get worse. Patients’ lungs inflame, cutting off air to their alveoli, the small sacs where our blood acquires oxygen and disposes of carbon dioxide. They may also fill with fluid, causing pneumonia.

Now, that’s not to say that eliminating air pollution would eliminate the risk of similar pathogens wreaking havoc in the future. But if the pristine lung hypothesis bears out, cutting pollution could reduce the severity among the most at-risk.

Featured image by 云中君/Wikimedia Commons (CC BY), satellite image by NASA and ESA.